New system developed for wearable devices that can detect stress

Using silver

wire network on a stretchable material, scientists have developed a device that

senses strain, mimics pain perception and adapts its electrical response

accordingly. By recreating these pain-like responses, the device paves the way

for future smart wearable systems that can help doctors detect stress.

In today's world, technology that can feel and adapt like

human senses is increasingly valuable. Areas ranging from healthcare to

robotics, needs materials that can "sense" stress or pain. They can

enhance safety, make wearable tech smarter, and improve human-machine

interactions.

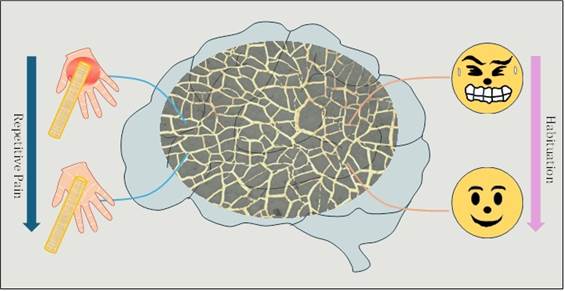

Neuromorphic

devices—technology inspired by the brain—gives ideas about how the human body

senses and responds to pain. In our bodies, special sensors called nociceptors detect

pain and help us respond to harmful situations. Over time, with repeated

exposure, one can actually feel pain less intensely through a process called

habituation.

Scientists from Jawaharlal Nehru Centre for Advanced

Scientific Research (JNCASR), Bengaluru, an autonomous institute of Department

of Science and Technology were inspired by this idea and ventured to create a

sensor that not only detects strain but also adapts and “learns” from it. Using

a network of tiny silver wires embedded in a flexible, stretchable material

they developed a material that can sense strain and adjust its response over

time.

When the material is stretched, small gaps appear within

the silver network, temporarily breaking the electrical pathway. An electric

pulse can then prompt the silver to fill these gaps, reconnecting the network

and essentially "remembering" the event. Each time it is stretched

and reconnected, the device gradually adjusts its response, much like how our

bodies adapt to repeated pain over time. This dynamic process enables the

device to mimic memory and adaptation, bringing humans closer to materials that

respond intelligently to their environment.

The

device sets itself apart by combining sensing and adaptive response in a

single, flexible unit and offers a streamlined, efficient way for technology to

adapt to its environment naturally, without complex setups or external sensors.

The research published in the journal Materials Horizons,

Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC) could lead to more advanced health monitoring

systems that "feel" stress like the human body and adapt in

real-time, giving feedback to doctors or users. Such technology could also

improve robotic systems, helping machines become safer and more intuitive to

work with humans.